This post was provided by Phil Walter, a former Infantryman, Intelligence Officer, and Counterterrorism Planner. Phil currently serves in a policy role in the Executive Branch of the United States Government. The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not contain information of an official nature.

Listen closely and you can hear it. Far off in the distance an angry mob has formed and wants the heads of every intelligence organization across the United States Government on pikes. The stale mantra of “intelligence failure” and “strategic surprise” has returned. This time, the stimulus is the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) which then became the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and is presently called the Islamic State (IS). Before we can discuss the intelligence focus or lack thereof on the recent events in Iraq and Syria, we need to establish a baseline of knowledge.

The United States Intelligence Community website states, “Our primary mission is to collect and convey the essential information the President and members of the policymaking, law enforcement, and military communities require to execute their appointed duties.” Another portion of the webpage describes the intelligence cycle and how “[t]he process begins with identifying the issues in which policy makers are interested and defining the answers they need to make educated decisions regarding those issues.”[i]Note the part where the issues of interest are identified. Intelligence is a support function to something larger. That something larger is the effort undertaken by the customer who consumes the intelligence.

Despite the money spent and hours worked, there will always be a gap between customer expectations and the capability of the intelligence organization that supports them. Intelligence organizations are not omnipotent nor are they omnipresent. Products generated by intelligence organizations do not cure all ailments nor do they serve a Tabasco sauce-like role by making even the worst meal more palatable. Customers should understand that the intelligence organizations supporting them are manned by dedicated professionals collecting and analyzing inconceivable amounts of information, some of which may be conflicting or have veracity issues, and struggling to synthesize it into a useful and meaningful document free from bias.

The success of an intelligence organization is tied to the direction it receives from its customers. If the customer doesn’t direct its intelligence organization to focus in depth on Syria then one should not be angry when events in Syria seem surprising. The intelligence organization to customer relationship is also a two way street. If direction does not materialize, the intelligence organization must demand direction from its customer.

When General Stanley McChrystal became Commander of U.S. forces and the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan in June 2009, his approach differed from that of his predecessors. Rather than focusing on the targeting process of find, fix, finish, exploit, analyze, and disseminate (F3EAD),[ii] General McChrystal’s strategy put the protection of civilians first and the killing of the enemy second.[iii] Accompanying General McChrystal to Afghanistan was Major General Michael Flynn who served as Director of Intelligence. Major General Flynn soon realized that the intelligence needed to support General McChrystal’s strategy was lacking as it was apportioned to support F3EAD instead of military operations to protect civilians.

Major General Flynn, along with Captain Matt Pottinger, United States Marine Corps, and Paul D. Batchelor, Defense Intelligence Agency, noted the disconnect between customer needs and intelligence community apportionment in a January 2010 paper “Fixing Intel: A Blueprint for Making Intelligence Relevant in Afghanistan.” A relevant quote from that paper is, “Eight years into the war in Afghanistan, the U.S. intelligence community is only marginally relevant to the overall strategy. Having focused the overwhelming majority of its collection efforts and analytical brainpower on insurgent groups, the vast intelligence apparatus is unable to answer fundamental questions about the environment in which the U.S. and allied forces operate and the people they need to persuade.”[iv] To protect civilians, one must understand civilians. Major General Flynn’s paper attempted to persuade the intelligence community, an organization over which the Department of Defense has little control, to apportion themselves to meet the needs of General McChrystal’s strategy.

Once the customer provides direction to the intelligence organization, the process of risk management begins. Intelligence organizations have limited manpower, budgets, and time. Based upon this, intelligence organizations cannot be masters of all domains. If an intelligence organization is going to focus in depth on issue X, it will likely have to focus less on issue Y. To borrow from Sun Tzu, “Preparedness everywhere means lack everywhere.”[v]

Once direction has been provided and risk management decisions have been made, it is now time to turn the properly apportioned intelligence organization loose to do its job. Depending upon the particular intelligence discipline, this can happen quickly or extremely slowly. The more technical intelligence disciplines can likely change their focus faster than slower ones such as human intelligence.

When a world event occurs it is common for a customer to ask his intelligence organization, “What do we know about this event?” This is a legitimate question. It is also a very basic question. A more advanced line of questioning would be, “How is my intelligence organization apportioned to meet the intelligence requirements associated with this world event? Do I need to shift a portion of my intelligence organization’s capability away from its current focus and onto this world event? If I do so, what risks do I assume?” Successful intelligence efforts are based upon strong relationships between customers and their intelligence organizations. The conditions for success exist when these relationships involve openly discussing direction, risk management, and apportionment of capability.

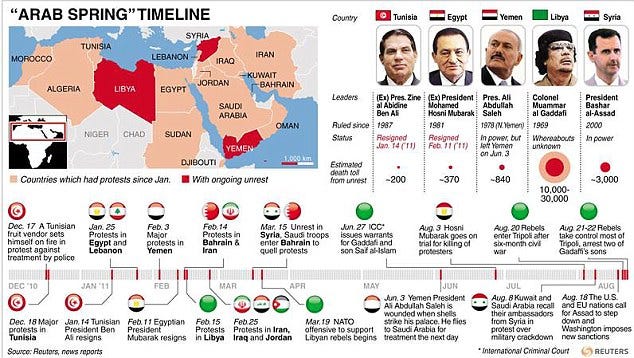

So what led to our current situation where cries of “intelligence failure” and “strategic surprise” are rampant? It was likely a convergence of circumstances. The events that led to the Syrian civil war, which in turn contributed to the rise of ISIL, began in March of 2011.[vi]In March 2011, other world events included Egypt appointing a new Prime Minister, the Libyan civil war being underway, President Saleh in Yemen refusing to step down, and thousands protesting in Bahrain.[vii]Based upon world events it is likely that the situation in Syria simply didn’t warrant much attention at that time.

So what led to our current situation where cries of “intelligence failure” and “strategic surprise” are rampant? It was likely a convergence of circumstances. The events that led to the Syrian civil war, which in turn contributed to the rise of ISIL, began in March of 2011.[vi]In March 2011, other world events included Egypt appointing a new Prime Minister, the Libyan civil war being underway, President Saleh in Yemen refusing to step down, and thousands protesting in Bahrain.[vii]Based upon world events it is likely that the situation in Syria simply didn’t warrant much attention at that time.

In over three years since, it is possible that direction, risk management, and apportionment of intelligence capability did not occur. Even if all three did occur, something else could have happened. Warnings could have been ignored by customers. Sherman Kent, who the Central Intelligence Agency calls the Father of Intelligence Analysis, believed that warning is not complete until the Warner warns and the Warnee hears, believes, and acts.[viii] Despite the best efforts of intelligence organizations across the United States Government, they cannot make their customers choose action over inaction.

[i] Intelligence.Gov — Collaboration. Commitment. Courage. (n.d.). Retrieved October 1, 2014.

[ii] Gomez, J. (2011, January 1). The Targeting Process: D3A and F3EAD. Retrieved October 1, 2014, fromhttp://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a547092.pdfhttp://www.defense.gov/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=55055

[iii] United States Department of Defense. (2009, July 8). Retrieved October 1, 2014, from http://www.defense.gov/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=55055

[iv] Flynn, M., Pottinger, M., & Batchelor, P. (2010, January 1). Fixing Intel: A Blueprint for Making Intelligence Relevant in Afghanistan. Retrieved October 1, 2014, fromhttp://www.cnas.org/files/documents/publications/AfghanIntel_Flynn_Jan2010_code507_voices.pdf

[v] Cleary, T. (1991). Emptiness and Fullness. In The Art of War by Sun Tzu.Shambhala Pocket Classics. Retrieved October 1, 2014, fromhttp://web.mit.edu/~dcltdw/AOW/6.html

[vi] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. (n.d.). Syrian Civil War (Syrian history). Retrieved October 1, 2014, fromhttp://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1781371/Syrian-Civil-War

[vii] March 2011 Current Events: World News. (n.d.). Retrieved October 1, 2014, from http://www.factmonster.com/news/2011/current-events/world_mar.html

[viii] Davis, J. (n.d.). Sherman Kent’s Final Thoughts on Analyst-Policymaker Relations. Retrieved October 1, 2014, fromhttps://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/kent-csi/kent-vol2no3/pdf/v02n3p.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment