Outer space exploration has turned into a key part of a modern society’s functionality with several services including weather, communication, Internet, banking and navigation, supported by satellites orbiting the Earth. India being one of the major actors in outer space has in many ways led the usage of satellites for the benefit of the society. With the space infrastructure of India powering the economy, is there a case for exploring the defence of these vital systems? Moreover, given that the geopolitics and security scenarios are changing with respect to the utilisation of outer space, should India explore its capabilities and capacities built in the country for the past 50 years for dedicated space defence operations? The present work provides insights on the key question as to are we or are we not at a tipping point where the government needs to draw a vision in securing national interests via creation of a Defence Space Agency as an interim arrangement until a full-fledged Aerospace Command is in place. If so, what are its technological, organisational and policy facets?

Outer space exploration has turned into a key part of a modern society’s functionality with several services including weather, communication, Internet, banking and navigation, supported by satellites orbiting the Earth. India being one of the major actors in outer space has in many ways led the usage of satellites for the benefit of the society. With the space infrastructure of India powering the economy, is there a case for exploring the defence of these vital systems? Moreover, given that the geopolitics and security scenarios are changing with respect to the utilisation of outer space, should India explore its capabilities and capacities built in the country for the past 50 years for dedicated space defence operations? The present work provides insights on the key question as to are we or are we not at a tipping point where the government needs to draw a vision in securing national interests via creation of a Defence Space Agency as an interim arrangement until a full-fledged Aerospace Command is in place. If so, what are its technological, organisational and policy facets?

The case for India’s utilisation of outer space has traditionally been to “harness space technology for national development, while pursuing space science research and planetary exploration”.[1] Today, the global space economy is a key part of modern society infrastructure, providing connectivity, insights of the Earth from space and navigational support. In terms of financials, the space economy grew by 9 percent in 2014, reaching a total of $330 billion worldwide, with commercial space activities making up 76 percent of the global space economy with a growth of 9.7 percent (2014).[2]

India, very much a part of the global space economy, has matured to be one of the key actors in outer space; and is one of those that reap benefits of infrastructure in space with the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) operating one of the biggest fleets of satellites (remote sensing, satellite communications and navigation) in the world. Today, India’s space programme is valued at more than $2.3 billion in assets already in orbit; this figure rises to around $37 billion ground-based infrastructure and value-added services are included.[3]These satellites have facilitated governance, harnessing the advantages of space for its citizens.

However, given the changes in the international and regional security and geopolitics of outer space over the past two decades, one might argue that India needs to consider utilising its space capacities for securing its regional and territorial interests and the safety of its space infrastructure. Some steps in this regard have already been taken in an incremental style.

The first such concrete step was taken in 2010 with the creation of an Integrated Space Cell (ISC) under the Integrated Defence Services (IDS) Headquarters of the Ministry of Defence. The ISC has had a coordinating role between armed forces as well as with the Department of Space and Ministry of Defence for greater integration of space technology and assets into military operations.[4] Following such developments, for the first time, ISRO built and launched dedicated military communications satellites, GSAT-7 (2013) for the Navy and GSAT-6 (2015) for armed forces.[5] Further, the Technology Perspective and Capability Roadmap (TPCR) of the IDS details several space-based capabilities envisioned for India’s expanding space-based security needs.[6]

With this dedicated infrastructure in outer space, experts within space security have signalled the threat to these assets due to our reliance on them.[7]

From technological, organisational and political perspectives, India needs to take a stand in active utilisation of outer space for meeting its security interests and affirming its position among the global space community in providing a transparent regime to utilise outer space for national security. Therefore, given the evident movement in utilisation of space systems for space-based security interests, formation of a dedicated defence space establishment in India seems a logical step in taking charge of these advances.

Facets of a Defence Space Establishment

Following recent turn of events, there has been a movement towards opening up India’s space security by a possible creation of a Defence Space Agency (DSA) as an interim arrangement until a full-fledged dedicated Aerospace Command is in place.[8] This seems a case for the expansion of ISC for a more active role in utilisation of outer space within the armed forces. The case for a defence space establishment is not just of adding a final frontier edge to warfare or adding theatre capability via space assets to the armed forces. It is about developing a multi-dimensional approach to using outer space for strategic purposes.

Establish minimum technology umbrella: While creation of a DARPA-like agency in India may be thought off as a moon-shot, there is tremendous scope to establish certain minimum technology capacity umbrella that is at par with that of advanced militaries and spacefaring nations. This minimum technology umbrella will not only feed into the current requirements but also act as a catalyst to spin-off advanced requirement concepts for the future.

Space security doctrine: Declaring a space security doctrine that encompasses the military space utilities as well as spelling out the conditions under which India will consider the offensive and defensive use of space should be a priority. The doctrine should also factor in India’s internal security challenges, including surveillance of the vast coastlines, porous border areas and other insurgency-related issues.

Capacity building in the industry: With the recent opening up of markets with a much more conducive environment via foreign direct investment, there are institutional challenges within the system that need to be addressed. While the private sector is now trying to move ahead with investments, there are still a lot of challenges in building up capacity in the private sector for it to deliver turnkey-level solutions for large/complex systems. One of the big challenges, however, is to strike a balance between the public and the private sector so that they co-exist without any conflict of interest.

Long-term roadmap & foundation for next generation systems: While the TPCR provides some sense of what space-based capabilities are of interest in the realm of defence and security, there is a need to develop a dedicated long-term roadmap for space security in India. One can draw inspiration from ISRO in developing such decade-long roadmaps and meeting technical challenges systematically in an effort to meet long-term goals. There is a need to develop mechanisms for the promotion of home-grown innovation in defence space systems (both in public and private sector) that will enable India to leapfrog in technologyand to build next generation systemsthat provide an edge in Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Information, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (C4I2SR).

Technological Capacity Interests

With the seed sown for space exploration right from the first satellite flown in 1957—being driven via defence interests—time and again, space capabilities have proven to bring an additional dimension to traditional defence capabilities that can support C4ISR.

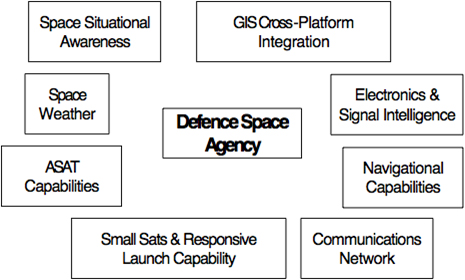

Figure 1 reflects minimum baseline technological capacities that need to be established to have an effective foundation in integration of space capabilities into the various military functions. Completing such an array of technological capacity requirements shall have a multitude of effects on speed, accuracy & precision of information collection, strategic planning & decision making, integration of technology to gain battleground superiority across the different forces and platforms. Each of these identified technological capacity has been detailed further to provide insights into their operational use from a strategic user perspective.

Figure 1. Technological Capacity Interests of Defence Space Agency

Space Weather

With growing number of space assets, one of the major fields of growing importance to monitor the health and safety of all systems in space and their allied equipment on the ground is tracking space weather. This has emerged as a part and parcel of Space Situational Awareness (SSA), with a broad scope of monitoring and predicting near-Earth space environment that can degrade and disrupt the performance of technological systems due to adverse conditions caused by activities such as solar storm.

Space weather has gained such prominence that several spacefaring nations have developed preparedness strategies for space weather exigencies. For example, the Unither Kingdom has a National Space Security Policy (NSSP) whose objectives include resilience to the risk of disruption to space services and capabilities; and has developed a Space Weather Preparedness Strategy.[9]

There are several mapped impacts of space weather situational awareness on the ability to use space assets for missions which include communication and navigation, among others. From a space command and control perspective, these include decreased operational payload utility, decreased ability to control satellites, and loss of satellite tracking. From an ISR perspective, it would mean inaccurate position data or loss/degradation of intelligence due to radio frequency interference, range uncertainty, loss of target discrimination, spectral distortions, degraded system performance, reduction in resolution of SAR images due to solar flares, and ionospheric storms. From a SatCom and long-range communications perspective, these would be inability to exercise C2, inability to send evacuation with life of small teams at risk. From a positioning, navigation and timing perspective, these include loss of navigation and manoeuvring accuracy for precision-guided munition, and decreased ability to synchronise ops with precision timing.[10] Given these risks at large from space weather, there is a need to expand the scope of understanding the scientific phenomenon of space weather to turn around the knowledge of these effects (spacecraft charging and ground effects) to design inputs and operational strategies for critical systems,[11] especially communications and positioning.

EO Small Satellites & Responsive Launch Vehicle

One of the major areas of low Earth orbit (LEO) exploitation in the recent times is in building low-cost small satellite (

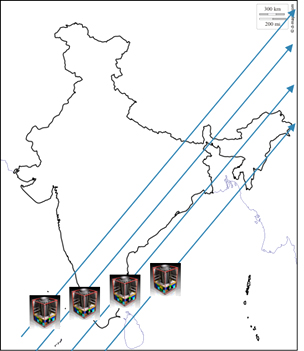

Figure 2 provides an overview of a small satellites constellation in orbit. While having very high resolution satellites such as CartoSat 2C in orbit shall provide capabilities of mapping up to 0.65 m resolution on the ground, these satellites are expensive and can only be launched one at a time, and they provide a revisit of about four days. Therefore, there is a strong case to deploy a constellation of small satellites that can support

Figure 2. Small Satellites in Constellation

Moreover, these networks of small satellites can also be launched on demand with retrofitting on Agni-5 with mobile launching capabilities. This has the potential to be developed as a responsive launch capability programme where a network of six to eight satellites can be launched on one rocket through a single plane to provide excellent coverage in swath. As far as coverage is concerned, a CARTOSAT provides coverage of about 10 km swath in a single satellite. However, having a network of these satellites on a single plane with an adjusted phase angle difference can provide a combined swath of 60-80 km, which has immense potential for exploitation in image intelligence. One has to also note the possible exploration of such a constellation in two or multiple orbits (one in polar sun synchronous and other in a slightly inclined orbit) to exploit security interests around the borders.

Moreover, these networks of small satellites can also be launched on demand with retrofitting on Agni-5 with mobile launching capabilities. This has the potential to be developed as a responsive launch capability programme where a network of six to eight satellites can be launched on one rocket through a single plane to provide excellent coverage in swath. As far as coverage is concerned, a CARTOSAT provides coverage of about 10 km swath in a single satellite. However, having a network of these satellites on a single plane with an adjusted phase angle difference can provide a combined swath of 60-80 km, which has immense potential for exploitation in image intelligence. One has to also note the possible exploration of such a constellation in two or multiple orbits (one in polar sun synchronous and other in a slightly inclined orbit) to exploit security interests around the borders.

ASAT Capabilities

Following the Chinese ASAT missile test destroying an unused weather satellite in January 2007,[12] there has been a debate on India’s ability to develop and demonstrate ASAT capabilities, which can act as a deterrent against such adversaries in the final frontier. India recognises such tests as a threat to all space assets as well as being against the spirit of non-weaponisation & peaceful usage of outer space.[13]

While most of the ASAT tests have been performed in LEO, there is speculation of China performing long-range ASAT tests that could threaten Medium Earth Orbit (MEO) and Geostationary Earth Orbit (GEO) satellites.[14] From a 21st century strategic perspective one can argue that in advanced threat scenarios, assets in LEO—which typically are into Earth Observation (EO) and remote sensing missions—are more dispensable against assets providing navigational and communications capabilities from MEO and GEO. Removing the navigation and communications capability from space can have a crippling effect for large-scale military operations.

From an Indian perspective, it is quite clear from several official statements at UN forums, such as the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva, that it is against weaponisation of outer space.[15] However, India’s stand on conducting ASAT tests is unclear. There are concerns that if it does not demonstrate such a capability, it will be left behind facing a repeat of what happened in the nuclear domain.[16]

While India does have the fundamental building blocks for a kinetic-kill full-fledged ASAT weapon based on Agni and the ballistic missile interceptor, showcasing this capability has to be done in a responsible manner without creating huge amount of long-lasting debris that could damage existing satellites.[17] A possible template to showcase technological capabilities may lie in following a strategic engagement of a low-flying asset that may not sustain any in-orbit debris but will completely be destroyed in entry and upper atmosphere. US performed such a mission as recently as 2008, launching a single Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) and destroying a 5,000-pound satellite with nearly 100 percent of the debris safely burned-up during re-entry within 48 hours and the remainder safely re-entering within the next few days.[18] One has to note that India does not have any space asset at such a low altitude; and if such a capability has to be demonstrated, one of the dying satellites will have to be lowered to perform such a test.

While the policymakers may choose to make concrete decisions on such matters reactively, technologically the focus should be on having long-range tracking capabilities, on-ground development of technological building blocks to increasing reach to MEO & GEO, and systems of denial of service. Long-term technology focus can definitely pursue the potential of exploiting non-kinetic kill options by exploring cyber or focussed high-energy techniques.

Signal Intelligence

The need for satellite-based signal intelligence due to limitations of ground-based equipment (owing to radio horizon as well as such an equipment being compromised in advanced threat scenarios due to attack) is real. The field of satellite-based Signal Intelligence (SIGINT) encompasses Communications Intelligence (COMINT) with a focus on interception and decryption of military and strategic communications, Electronic Intelligence (ELINT) with a focus on developing technology for radio signals interception and decryption. The scope of SIGINT has also expanded towards capturing of telemetry signals with a special focus on missiles.[19]

At present, India has extremely limited space-based COMINT capabilities with two GEO satellites supporting strategic communications with the multi-band communication satellite GSAT-7and GSAT-6.[20]

However, China not only has full-fledged secure satellite communications networks, but also has expanded its satellite capabilities and may very well be equipped to use its network of LEO and GEO satellites to accurately track and target naval assets in near-real-time as part of its satellite-aided Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile (ASBM). Similarly, from an air-defence perspective, ELINT capabilities may be used to precisely locate air defence systems, making such systems vulnerable.[21] The Yoagan constellation launched by the Chinese is said to have capabilities of providing 16 targeting opportunities with less than 10-km location uncertainty for ballistic missile launch.[22]

Given the modernisation of armed forces and the increased air and maritime interests, India should at least establish a minimum ISR capabilities starting with three dedicated satellites and expanding to six with wide band receivers to be able to monitor activities in the Indian Ocean and South China Sea. Use of an array of space-based sensors, along with other sensors using common standards and communication protocols for transmitting information automatically through machine-to-machine interfaces, are important. These become useful in the context of missile targeting as well as establishing data links in a multiple platform/command & control scenario.

GIS Cross Platform Integration

Geographic Information System (GIS) is a powerful tool to combine various spatial, spectral and other sources of data to generate key insights for security stakeholders. With the ever-increasing computational power alongside the increase in the number of sensors available, utilisation and integration of GIS into specific scenarios and actual traditional battlefield systems (such as UAVs, tanks, submarines, aircraft, etc.) will provide an edge over adversaries.

Post 9/11, US floated a dedicated National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) in 2003 to provide geospatial intelligence putting policymakers, military, intelligence professionals and first responders at a decisive advantage.[23] This dedicated agency claims to have helped track down al Qaeda leader Osama bin Ladin and shared insights with the special operations team that successfully stormed his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan.[24]

Tracking and visualisation of insurgent attacks based on their use of the geography, terrain, population density, and infrastructure with different mathematical models can be used to combat guerrilla warfare.[25] This has tremendous scope for exploration from an internal security perspective for India.

Dedicated tools in GIS have been explored for coastal security by combining several data sources such as high-resolution images, Lidar, conduct of fleet/vehicle mobility analysis, continuous sea–land Digital Elevation Model (DEM) and geo-visualisation of changing shorelines with tidal levels in an effort to build a Littoral Warfare Database that enables commanders to take feasible and realistic decisions.[26]

With the exponential dispersion of sensors (both in space, on ground and below) and emergence of technologies such as IoT/M2M, fusing all such data alongside GIS information will hold the key to taking intelligent decisions. There is no doubt that cross-platform integration of GIS technology as well as on-ground decision intelligence support system are the very basic needs of an effective network-centric warfare strategy.

Navigational Capabilities

India has completed the Indian Regional Navigation Satellite System (IRNSS) constellation for providing accurate position information to users in India as well as the region extending up to 1500 km from its boundary.[27] This constellation can be used to aid in navigation for missions on land, in sea and in air; and can very well serve as an invaluable component of network-centric warfare.

While India is undertaking modernisation of its defence equipment, the integration of indigenous navigation systems at the user segment of these equipment will definitely be an important step towards self-reliance in defence technology. Typical examples of such uses shall be in the ballistic missile programmes such as Agni, and cruise missile programme such as BrahMos.[28] The indigenous navigational capabilities have a wide array of other uses also, of course, outside of strategic areas—from most mundane such as location devices for infantry to smart bombs, covert surveillance and armoured warfare.

Space Situational Awareness

Satellites form an important part of network-centric warfare and therefore are prone to a broad range of natural disasters and intentional attacks, including cyber-attacks, space weather, space debris, collisions with other satellites and ASAT attacks. Therefore, it is necessary to have a military space situational awareness capabilities to not only track objects in space but also map the capabilities of various space systems and their implications for national security.

India right now has limited capabilities in the field of space situational awareness, with major asset for tracking objects such as space debris being carried out by ISRO’s Multi-Object Tracking Radar (MOTR).[29] While tracking is a major portion of space situational awareness, ground-based radar tracking may provide real-time collision analysis, given the cataloguing of the location and orbital information about all space objects. However, from a military dimension, there is a need to develop space-based systems that can help determine the capabilities of various space systems in-orbit and the intentions of its owner.

Internationally,there have been recommendations made to develop radar-independent tracking methods such as lasers, coherent infrared sensors as well as developing space systems with a sole purpose of tracking the functional capabilities of suspected satellites that may serve the military functions.[30]

A dedicated space situational awareness initiative within the defence space agency can serve for gathering space-based network-centric intelligence capabilities of adversaries and shall help map out evolving ground-based counter-capabilities. .

Communications Capabilities

The current satellite communications platforms for defence operations are served by GSAT-7 for Navy[31] and GSAT-6 for the armed forces.[32]

One of the significant areas to explore COMINT from a defence space perspective is its ability to exploit GEO platforms for data relay services for UAVs or other airborne platforms. Such airborne platforms can send their observation to a data relay satellite in GEO via an optical link. Subsequently, the satellite-based data relay services via high-speed laser communication can be used to replace expensive network of ground stations needed to constantly receive LEO satellite data.Moreover, there is also scope to explore inter-satellite links between GEO satellites that can be used to share resources and/or route traffic around a satellite network. In order to effectively exploit space, India also needs to focus on having orbital slots available in GEO, which shall be critical to have the necessary authorisation by International Telecommunications Union (ITU) to place satellites over the Indian-subcontinent.

Logic for A Space Security Doctrine

India’s space programme has grown enormously over the past decade but without a broad strategic plan because India has lacked an overall strategic doctrine that lays out its long-term goals and objectives. As India’s power and influence rises, there has to be greater clarity on what it wants to achieve as a nation in its overall security as well as within each of the important security domains such as nuclear and outer space.

India has many external security challenges, from cross-border terrorism and internal insurgencies to unresolved border and territorial issues, all of which call for a huge defence-space requirement. Repeated terrorist attacks in India, including on sensitive military installations, point to the need to better integration of space technology for military functions such as reconnaissance, and safe and secure communication channels, which put a premium on India’s space capabilities. While space utilisation has picked up in the backdrop of these challenges, these are still being done in a haphazard manner.

India must also outline its red lines in space, that is, under what circumstances offensive use of space will be sanctioned. These must be laid down in clear terms to bring about clarity within the Indian establishment but also clarity in the minds of the adversary as to what is considered permissible behaviour and what might provoke a military response (intentional jamming and blinding, destruction, interference). This should include, for instance, a code of conduct and standard operating procedures for any threat to Indian space assets to avoid ambiguities.

The doctrine must also spell out how space assets will be put to use to deal with the internal security of India. The internal security challenges are very vast and these include surveillance of the cross-border areas, monitoring of the vast coastlines and water spaces, and monitoring naxal-affected areas. The cyber-outer space interface is another set of challenges that need to be factored within the doctrine. The growing linkages between cyber and outer space domains present India with new challenges, and India should develop a set of considered options that would protect against its vulnerabilities in space.

Space Security Strategies and Policy

Having established itself as a major space power, what India lacks is an overarching strategy that guides its space programme. In the absence of such a strategy, India’s space programme and ISRO’s attempts to cater to the wide-ranging demands have represented more of a piecemeal approach. India has to factor in the growing requirements of the space assets in social, economic and security arenas. A space security strategy will synchronise these growing requirements, taking into account India’s total capacity, including political and economic capital. National space security strategy should also include the command and control structures to implement and respond to situations identified in the doctrine such as offensive uses of space and maintaining space deterrence.

Audit of Technology Integration and Performance

Even as ISRO has done a splendid job with India’s space programme, there has to be better accounting and auditing of the technological developments and, more importantly, technology integration and performance. Providing constant insights on the performance of the programmes, the direction of the organisation, insights from an international technology and geopolitical perspective through a parliamentary oversight group or government-funded defence think tanks—such as the Institute for Defence and Strategic Analyses (IDSA), Centre for Air Power Studies (CAPS)—can be done via a dedicated Task Force created within the DSA for this purpose.

Conclusion

While there are significant opportunities to integrate satellite-based technologies into the defence realm, there is a need to carefully plan this technology integration. Given that DRDO does not focus its efforts on development of satellite platforms, there is tremendous opportunity for Indian industry to invest into such platforms.

Moreover, the defence space agency can act as an observer and regulator, which will constantly assess the needs of the armed forces and executes those needs via the industry. This provides a win-win situation for both the armed services and the local industry. This also ensures that there is scope for long-term capacity building in the country that can foster export of turnkey solutions for satellite-based products and services from India. Further, this will serve as a method of fruition of the tremendous efforts put forth by ISRO to develop a local industry ecosystem over the past 40 years.

Additionally, wherever there are gaps in state-of-the-art technologies, there is tremendous scope to explore closing such gaps with models such as international JVs under initiatives such as ‘Make in India’.

From an organisational coordination perspective, there is a need to setup a clear protocol for coordination of defence space use between already established institutions—such as Defence Image Processing and Analysis Centre (DIPAC), Aviation Research Centre (ARC), National Technical Research Organisation (NTRO), Defence Intelligence Agency (DIA), Defence Satellite Control Centre (DSSC), and Research and Analysis Wing (R&AW). The critical aspect of the utilisation of the space dimension for intelligence gathering by these institutions can further elevate the quality of inputs to both investigative bodies as well as policymakers for internal and external security.

This article was originally published in ‘Defence Primer‘

[1] “Vision and Mission Statements,” Indian Space Research Organisation, accessed November 5, 2015, http://isro.gov.in/about-isro/vision-and-mission-statements.

[2] “The Space Report 2015: The Authoritative Guide to Global Space Activity,” The Space Foundation, accessed December 21, 2015, http://www.spacefoundation.org/sites/default/files/downloads/The_Space_Report_2015_Overview_TOC_Exhibits.pdf.

[3] S Chandrasekhar, “The Emerging World Space Order and Its Implications for India’s Security,” in Subrata Ghoshroy and Goetz Neuneck, South Asia at a Crossroads: Conflict or Cooperation in the Age of Nuclear Weapons, Missile Defense and Space Rivalries (Germany: NomosVerlag Publishers, 2010), pp. 219-220.

[4] Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan and Arvind K. John, “A New Frontier: Boosting India’s Military Presence in Outer Space,” Observer Research Foundation Occasional Paper 50 (January 2014), https://www.orfonline.org/cms/export/orfonline/modules/occasionalpaper/attachments/occasionalpaper50_1392021965359.pdf.

[5] Ajey Lele, “GSAT-6: India’s Second Military Satellite Launched,” Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, August 31, 2015, http://www.idsa.in/idsacomments/GSAT6IndiasSecondMilitarySatelliteLaunched_alele_310815.

[6] “Technology Perspective and Capability Roadmap (TPCR )” (Headquarters Integrated Defence Staff - Ministry Of Defence, April 2013), http://mod.gov.in/writereaddata/TPCR13.pdf.

[7] Sarah Knapton, “Star Wars: How Future World Conflicts Will Be Decided in Space,” The Telegraph, December 19, 2015, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/science/space/12058054/Star-Wars-how-future-world-conflicts-will-be-decided-in-space.html.

[8] Rajat Pandit, “India May Get Three Unified Commands for Special Operations, Battles in Space, on Web,” The Times of India, accessed October 27, 2015, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/India-may-get-three-unified-commands-for-special-operations-battles-in-space-on-web/articleshow/49399708.cms.

[9] “Space Weather Preparedness Strategy” (Cabinet Office & the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills in 2015, July 2015), https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/449593/BIS-15-457-space-weather-preparedness-strategy.pdf.

[10] Patrick Perron, “Space Weather Situational Awareness and Its Effects upon a Joint, Interagency, Domestic, and Arctic Environment,” Canadian Military Journal Vol. 14, No. 4 (Autumn 2014): 18–27.

[11] D. C. Ferguson, S. P. Worden, and D. E. Hastings, “The Space Weather Threat to Situational Awareness, Communications, and Positioning Systems,” IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 43, no. 9 (September 2015): 3086–98, doi:10.1109/TPS.2015.2412775.

[12] Brian Weeden, “2007 Chinese Anti-Satellite Test Fact Sheet,” Secure World Foundation, November 23, 2010, http://swfound.org/media/9550/chinese_asat_fact_sheet_updated_2012.pdf.

[13] Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, “India’s Changing Policy on Space Militarization: The Impact of China’s ASAT Test,” India Review 10, no. 4 (October 1, 2011): 354–78, doi:10.1080/14736489.2011.624018.

[14] Brian Weeden, “Anti-Satellite Tests in Space - The Case of China” (Secure World Foundation, August 16, 2013), http://swfound.org/media/115643/china_asat_testing_fact_sheet_aug_2013.pdf.

[15] Xiaodon Liang, “India’s Space Program: Challenges, Opportunities, and Strategic Concerns,” The National Bureau of Asian Research, February 10, 2016, http://www.nbr.org/research/activity.aspx?id=651.

[16] “Time for India to Join Global Space Rule Framing to Avoid NPT like Mistake, Say Experts,” The Financial Express, February 28, 2016, http://www.financialexpress.com/article/lifestyle/science/time-for-india-to-join-global-space-rule-framing-to-avoid-npt-like-mistake-say-experts/217044/.

[17] Sandeep Unnithan, “India Takes on China - Anti-Satellite Capability Can Target Space Satellites and Act as Deterrent against India’s Powerful Neighbours.,” India Today, April 28, 2012, http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/agni-v-launch-india-takes-on-china-drdo-vijay-saraswat/1/186367.html.

[18] “Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense : One-Time Mission: Operation Burnt Frost,” U.S. Department of Defense - Missile Defense Agency, accessed April 19, 2016, http://www.mda.mil/system/aegis_one_time_mission.html.

[19] Dr. R. Sreehari Rao, “Space Based Signal Intelligence Systems : Global Trends & Technologies - Defence Electronics Research Laboratory,” accessed April 19, 2016, http://indianstrategicknowledgeonline.com/web/space_sec_session%205_Sreehari%20Rao.pdf.

[20] Lele, “GSAT-6: India’s Second Military Satellite Launched.”

[21] Ian Easton and Mark A. Stokes, “China’s Electronic Intelligence Satellite Developments: Implications for U.S. Air and Naval Operations” (Project 2049 Institute, February 23, 2011), https://project2049.net/documents/china_electronic_intelligence_elint_satellite_developments_easton_stokes.pdf.

[22] Chadrashekar S. and Soma Perumal, “China’s Constellation of Yaogan Satellites & the ASBM : January 2015 Update” (National Institute of Advanced Studies, January 2, 2015), http://isssp.in/chinas-constellation-of-yaogan-satellites-the-asbm-january-2015-update/.

[23] “About NGA,” National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), accessed April 22, 2016, https://www.nga.mil/About/Pages/Default.aspx.

[24] “History,” National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), accessed April 22, 2016, https://www.nga.mil/About/History/Pages/default.aspx.

[25] Marcus Jermaine Carwell, “Examining the Impact of Environmental Variables on the Insurgent Behavior with the Aid of a GIS: Case Study of Afghanistan” (MORGAN STATE UNIVERSITY, 2014), http://gradworks.umi.com/36/26/3626239.html.

[26] S. Fleming et al., “GIS Applications for Military Operations in Coastal Zones,” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 64, no. 2 (March 2009): 213–22, doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2008.10.004.

[27] “Indian Regional Navigation Satellite System (IRNSS),” Indian Space Research Organisation, accessed April 22, 2016, http://www.isro.gov.in/irnss-programme.

[28] “IRNSS - The Military Importance Of A Desi-GPS,” Swarajya, accessed April 27, 2016, http://swarajyamag.com/ideas/irnss-the-military-importance-of-a-desi-gps.

[29] Ravikiran G., “With Multi-Object Tracking Radar, India Joins Big League,” The Hindu, May 16, 2015, http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/with-multiobject-tracking-radar-india-joins-big-league/article7212224.ece.

[30] Gene H. McCall and John H. Darrah, “Space Situational Awareness: Difficult, Expensive--and Necessary,” Air & Space Power Journal, December 2014, http://www.au.af.mil/au/afri/aspj/digital/pdf/articles/2014-Nov-Dec/SLP-Mccall_Darrah.pdf.

[31] Madhumathi D.S., “Navy’s First Satellite GSAT-7 Now in Space,” The Hindu, August 30, 2013, http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/navys-first-satellite-gsat7-now-in-space/article5074800.ece.

[32] Ajey Lele, “GSAT-6: India’s Second Military Satellite Launched.”

No comments:

Post a Comment