While there is much ado about China’s not-so-subtle efforts in the South China Sea to expand its borders, and to attain a level of influence that extends far beyond its own shores, the emerging superpower’s international strategy goes well beyond military objectives. China’s population may not be growing at a huge clip, but its rising middle class is responsible for an uptick in consumption habits as protein gobbles up a larger share of the country’s diet. While this may not seem so ominous, there are reasons for seeing it as a medium-term existential crisis for China’s governing class. This is a country, remember, in which ravaging famines are a not-so-distant memory and only 15 percent of the land is arable.

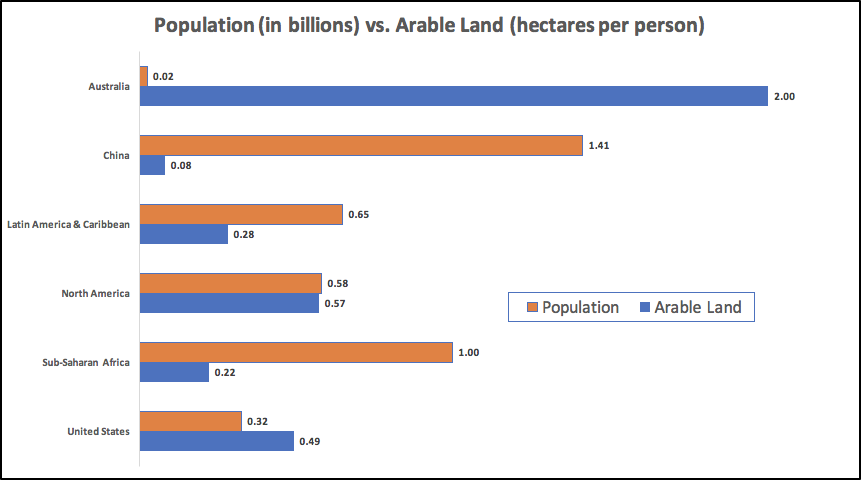

While there is much ado about China’s not-so-subtle efforts in the South China Sea to expand its borders, and to attain a level of influence that extends far beyond its own shores, the emerging superpower’s international strategy goes well beyond military objectives. China’s population may not be growing at a huge clip, but its rising middle class is responsible for an uptick in consumption habits as protein gobbles up a larger share of the country’s diet. While this may not seem so ominous, there are reasons for seeing it as a medium-term existential crisis for China’s governing class. This is a country, remember, in which ravaging famines are a not-so-distant memory and only 15 percent of the land is arable. Disparities in arable land vs. population give a clue to the evolution of global food security: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.ARBL.HA.PC?locations=CN

Disparities in arable land vs. population give a clue to the evolution of global food security: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.ARBL.HA.PC?locations=CN

Industrialization has wrought a punishing effect on China’s farmland. In an uncharacteristically blunt assessment, China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection indicated in a 2014 report that almost 20 percent of the country’s arable land is polluted. The worst of the affected soils were laced with inorganic chemicals such as nickel, cadmium, and arsenic — common mining by-products — while the remaining portions were rendered low yield due to heavy saturation from fertilizers and pesticides.

This, sadly, was not a shock to Chinese consumers, many of whom have cultivated a healthy distrust of domestically produced food items. Food scandals in China have ranged from melamine-tainted baby formula to recycled pig carcasses, creating large demand for imports of dairy and meat products from Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

Shanghai Husi Food Co., fined 17M yuan ($2.5M USD) for supplying repackaged older beef and chicken in 2014

Shanghai Husi Food Co., fined 17M yuan ($2.5M USD) for supplying repackaged older beef and chicken in 2014

The appetite for meat brings with it an increasing agricultural footprint — it takes about four times as much grain to feed animals like chicken, pigs, and cows. China now consumes half of the world’s pork.

This increasing demand drove Shuanghui International (now known as WH Group), a heavily subsidized Chinese pork producer, to purchase its American competitor, Smithfield Foods, for $7.1 billion in 2013. The purchase remains the largest Chinese acquisition of an American company to date. One in four American pigs is now produced by Smithfield for export to China.

Pigs are used in the famous Chinese dish Mao’s Pork Belly

Pigs are used in the famous Chinese dish Mao’s Pork Belly

Pork is such a critical part of China’s food security strategy that the federal government even created a strategic pork reserve — akin to the U.S. petroleum reserve — to protect against sudden declines in inventory. Reserves were “dropped” onto the market last year in Beijing to alleviate the impact of price spikes.

But if China’s demand for pork drives the country’s incremental restructuring of international agribusiness, beef is capable of shaping China’s acquisitional strategy to an even greater extent. According to OECD data, beef — the most ecologically expensive agricultural product to produce — experienced a 25 percent increase in consumption in China over the last six years.

Just as with Smithfield, that consumption trend drove the recent acquisitionof Australia’s Kidman cattle empire to Shanghai CRED. The Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE) finally settled a joint deal with Australia’s richest woman to buy over 1 percent of the continent’s land mass — the acreage is roughly the size of South Carolina — in one fell swoop. The purchase secured a herd of over 185,000 cattle in a belabored process that escalated all the way up to the country’s federal government.

The Smithfield and Kidman deals were followed this year by the acquisition of Syngenta by another Chinese SOE, ChemChina. The purchase adds to the company’s— and by extension the government’s — array of fertilizers, pesticides, and GMO seeds, and helps give it greater access to international food markets.

China’s orientation towards GMO corn impacts production practices in the United States and beyond

China’s orientation towards GMO corn impacts production practices in the United States and beyond

Currently China prohibits the importation and planting of GMO seeds, though it does allow the limited sale of the finished crops themselves. This June it approved two new strains of GMO corn and soybean produced by Dow Chemical and Monsanto, two U.S.-based competitive agribusiness corporations rumored to be working on their own merger in the quickly consolidating industry.

Free-market advocates may be encouraged by what they perceive as China’s increasing liberalization in the agribusiness industry. As the industry integrates into their domestic economy and China has a greater financial stake in it globally, many expect a greater enforcement of intellectual property protections to cover core elements of its product. This is seen as a helpful byproduct of the expanded economic cooperation.

Yet observers also warn of the increasing aggressiveness of the country’s economic posture through business and land acquisitions — actions that are swallowing up sizable chunks of the food supply across the world. They’re fearful that this is putting global food security at risk. As a result, they’re sounding alarm bells inside governments from Africa to the United States.

Functionally, China’s approach is an all-of-the-above strategy toward food security. China cannot compete like it does in manufacturing due to the geography it was dealt. And since its industries are guided by the state, it’s practical for them to integrate other nations’ agribusinesses into their own food supply.

But international consolidation alone is not enough; Chinese farming practices also need to evolve to help absorb the demands of its population in the coming decades.

In 2013, China’s Vice Minister of Agriculture, Han Changfu, said this at a meeting of the International Fund for Agricultural Development:

We shall continue to consolidate and strengthen agriculture; ensure food security; speed up the strategic restructuring of agriculture and rural economy; raise the integrated performance in agriculture; increase farmer’s income; and push forward the transformation of traditional agriculture into modern one with the aim of developing rural economy in an all-round way.

China has begun instituting some domestic reforms to encourage the consolidation of rural farm plots and even small villages into large corporate farms. Since farmland cannot be privately owned, farmers can effectively get their income from leasing their plots and indeed entire villages as well as being employed by the lessee. The non-coercive nature of the approach depends on what Han Changfu calls an “orderly transfer of land operating rights” that will enable the heightened efficiency of corporate farming.

A legendary “nail house” in Chongqing. Nail house owners refused to surrender land rights to the Chinese government for development projects.

A legendary “nail house” in Chongqing. Nail house owners refused to surrender land rights to the Chinese government for development projects.

Arable land is not a prerequisite for this agricultural revolution. According to the South China Morning Post, government engineers have begun the initial design of a tunnel to divert water from the Himalayan steppes of Tibet to the arid Taklimakan Desert in Xinjiang province 600 miles away. It would be the world’s longest tunnel, diverting some of the region’s 400 billion tons of annual water resources to create new farmland in a process that bypasses the complicated land transfers required in China’s interior.

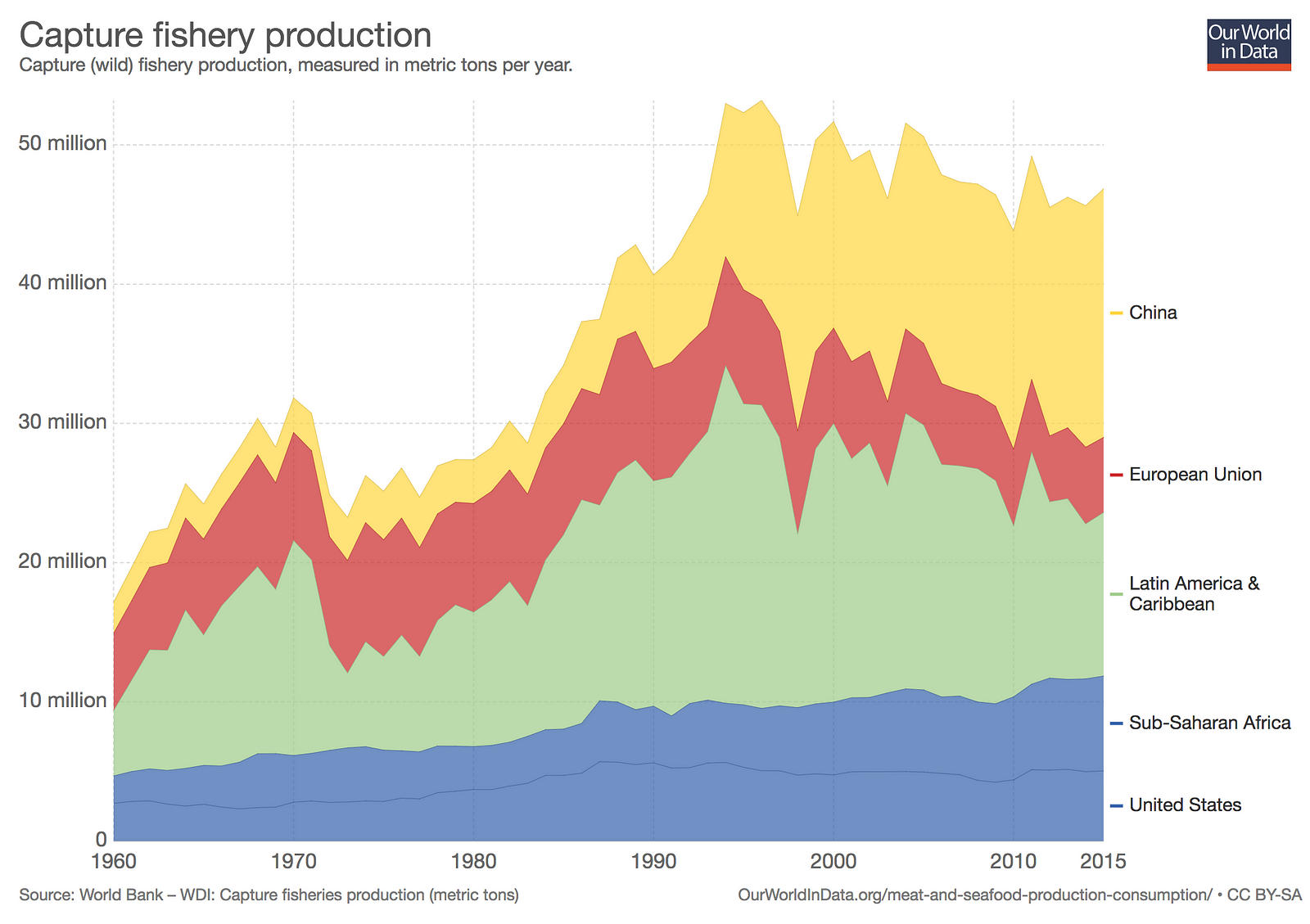

China matches its effort toward agricultural revolution with an aggressive approach to expanding its fishing to more of the world’s distant oceans. According to the New York Times, the Chinese fishing industry has benefited from heavy subsidization, allowing it to grow to a fleet of over 2,600 ships, 10 times that of the United States.

The efficacy of sophisticated Chinese fishing traulers has been stressing fish populations in less developed regions like coastal West Africa, and costing their domestic industry a reported $2 billion annually. According to the U.S. Department of Defense, they have also been used as a part of a “low intensity coersion” tactic in China’s regional waters.

China’s demand for food is a source of growth for global industry. It also presents unique challenges. As a larger percentage of the growing human population turns to ecologically expensive food products, suppliers must adapt by addressing efficiencies with their increasingly limited land. China is securing its food supply with a comprehensive strategy towards domestic and international markets and a willingness and growing ability to exploit the earth’s natural resources.

For China, food is not just economics — it’s national security. The tendency to view China as a geopolitical threat in this arena is not entirely unwarranted, but it begs a bigger question: What about the emerging middle class in the rest of the world? Emerging economies won’t always be “emerging”; they’ll eventually demand the diet of their first world neighbors. What will that mean for countries with higher per capita food production capacity? What about those who will be net importers?

A new dynamic is emerging, and it’s not about oil. China is just the stress test for how humanity feeds itself in the 21st century — and beyond that, how the earth will support us in the decades and centuries to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment