Turkey and Greece, two of the Mediterranean’s greatest rivals, have long sparred over dominance of the region. The center of gravity of this competition has been Cyprus, an island split between its Greek and Turkish occupants. The island has immense geostrategic value, sitting at the crossing of the Eastern Mediterranean’s main sea lanes, regional energy markets and trade routes. Control of Cyprus would give a country access to the island’s valuable natural gas reserves and exploratory drilling rights, helping it project itself as the dominant Eastern Mediterranean power. It’s for this reason that Turkey and Greece have accelerated their push to defend their maritime claims in the region. They have done so by employing two competing concepts that attempt to revive their imperial pasts: the Blue Homeland, a notion that harkens back to the Ottoman Empire’s glory days and that Turkey has used to justify expanding its reach farther into the Mediterranean Sea; and the Megali Idea, which implies Greek reestablishment of the old contours of the Byzantine Empire. These concepts are not just rhetorical; they are part of one of the most complex, entangled geopolitical rivalries today.

But the dynamics of the Eastern Mediterranean are also complicated by other factors. Russia, Syria, Iran and Libya all have interests there. And the growing competition in the region has increased paranoia among Mediterranean powers over sea lanes, navigation and energy resources. The end result has been a rush to delimit exclusive economic zones (regardless of legal parameters), formation of tighter alliances, escalation of the crisis in Libya and an emerging risk of military confrontation. The last time the Eastern Mediterranean was under such strain was in 1967, when the Soviet Union formed the 5th Mediterranean Squadron, causing an escalation in tensions between the Soviets and NATO member navies. With such significant geopolitical shifts emerging in the region, it’s necessary to take stock of its naval landscape: the players involved, their capabilities, their restraints and, most important, their intentions.

An Emerging Naval Power

With competition over offshore gas resources intensifying, Turkey has found it increasingly necessary to bolster its naval capabilities. The Turkish navy is considered one of the four strongest navies in the Eastern Mediterranean. (Greece, Israel and Egypt have the region’s other dominant maritime forces, and the U.S. Sixth Fleet and Russia’s Mediterranean Naval Force also have a commanding presence.) But over the past two decades, Turkey has pushed to expand its naval capabilities, particularly since tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean have escalated, indicating an increasingly ambitious Turkish naval agenda in the years to come.

For much of the 20th century, naval development was not a priority for Turkey. The inward-looking foreign policy of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and his successors, in addition to Turkey’s accession into NATO, led to a more limited naval strategy. Ankara didn’t feel the need to enhance its maritime capabilities beyond the ability to defend the Turkish Straits, the Sea of Marmara and the Aegean Sea. One of Ataturk’s key principles was “peace at home, peace in the world,” an isolationist motto that allowed Ankara to focus on domestic infrastructural and social reforms. The current government has attempted to change this, beefing up the country’s naval capabilities with an accompanying neo-Ottoman narrative led by the Blue Homeland concept, in an attempt to revive what it believes is Turkey’s rightful place as a key naval power in the region.

Geography, however, remains a key constraint in its naval development. The Turkish coastline is long, and the country’s access to the wider Mediterranean is restricted by a series of Greek islands, some located less than 45 miles (72 kilometers) from Turkish territory. The limited breathing room between Turkey and Greece makes it difficult for Turkey to focus on conventional naval capabilities, particularly since its primary imperative remains defense of its littoral waters. The Turkish navy therefore has mostly been geared toward coastal defense with a narrow set of operational capabilities.

Still, Turkey has an interest in pushing its buffer zone farther out into the Eastern Mediterranean. Since 2014, it has used gunboat diplomacy – the pursuit of strategic objectives through acts of intimidation at sea – to protect its seismic and exploratory drilling activities across the Eastern Mediterranean, as well as its maritime trade routes. (Turkey conducts 87 percent of its trade through its ports.) In fact, Turkey has been eyeing greater control of the Mediterranean since the 1970s. Its invasion of Cyprus in 1974, when it annexed 40 percent of the island in its first venture back into the Mediterranean since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, was a pivotal moment. Since then, several geopolitical “openings” have given Turkey room to flex its muscle in the sea. Greece’s financial crisis and inability to keep up naval defense spending opened the door for Turkish expansion in the region, while Ankara’s frustration with its dependence on foreign energy suppliers drove it to seek new sources of natural gas.

Turkey’s naval buildup has accelerated markedly in recent years. Its domestic industrial capacity has increased and its navy has been upgraded with retrofittings and new equipment, including cutting-edge propulsion, detection and navigation systems. Since 2007, the country has tripled its military research and development spending, which totaled $1.2 billion in 2018. Its defense budget totaled $19 billion in 2019, an increase of 24 percent over the previous year. In addition, Ankara has introduced the MILGEM program, an ambitious project to domestically produce frigates and corvettes for the Turkish navy. As an indication of just how ambitious this project is, the country plans to build 24 new ships – frigates, aircraft carriers (some compatible with the F-35B) and amphibious assault ships – and most are expected to be dispatched by 2023. The country is also developing six new, slightly longer-range submarines and a series of destroyers for larger, sustained campaigns in the Eastern Mediterranean. Its acquisition of these types of vessels indicates a continuing need for convoy escort missions, as they can accompany Turkish seismic drilling ships in contested continental shelves where there is a risk of conflict between Eastern Mediterranean adversaries. Turkey has also begun to promote its domestically manufactured equipment abroad in an effort to establish itself as a global arms exporter, which would give the country an economic boost and help it position itself as a Mediterranean industrial power. The expansion of Turkey’s defense industry is perhaps the single biggest development in Turkey’s naval advancement, which could pay dividends economically and strategically for years to come.

Ankara also hopes to begin adding more forward bases, including a naval base in Northern Cyprus, likely in the city of Famagusta close to the Iskele Strait. This base is the centerpiece of Turkey’s emerging maritime strategy, as it will allow Turkey to expand its naval logistics and drilling capabilities and conduct longer-range, long-term deployments deep into the Mediterranean. In addition, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus is renovating the abandoned Maras port in Famagusta at a cost of $10 billion, likely with Turkish support. The tempo of naval exercises has also increased. In early 2019, the Turkish navy hosted its second-largest drills, aptly named Blue Homeland, and conducted live-fire exercises in the Greek Cypriot exclusive economic zone. And in May, Turkey will host its largest naval drills, dubbed the Sea Wolf exercises, in the Mediterranean, Black and Aegean seas. These developments all serve a symbolic as well as a strategic purpose: They send a clear message to Turkey’s rivals – namely, Greece, Israel, Greek Cyprus and Egypt – that it is a force to be reckoned with.

The Bigger Picture

While all of these moves to boost Turkey’s naval power may indicate that Ankara is increasingly considering the risks of a large-scale conventional conflict in the Eastern Mediterranean, it’s important to keep in mind that Ankara’s primary focus remains closer to home, especially the defense of its own coastline and Cyprus from threats posed by Greece and its allies.

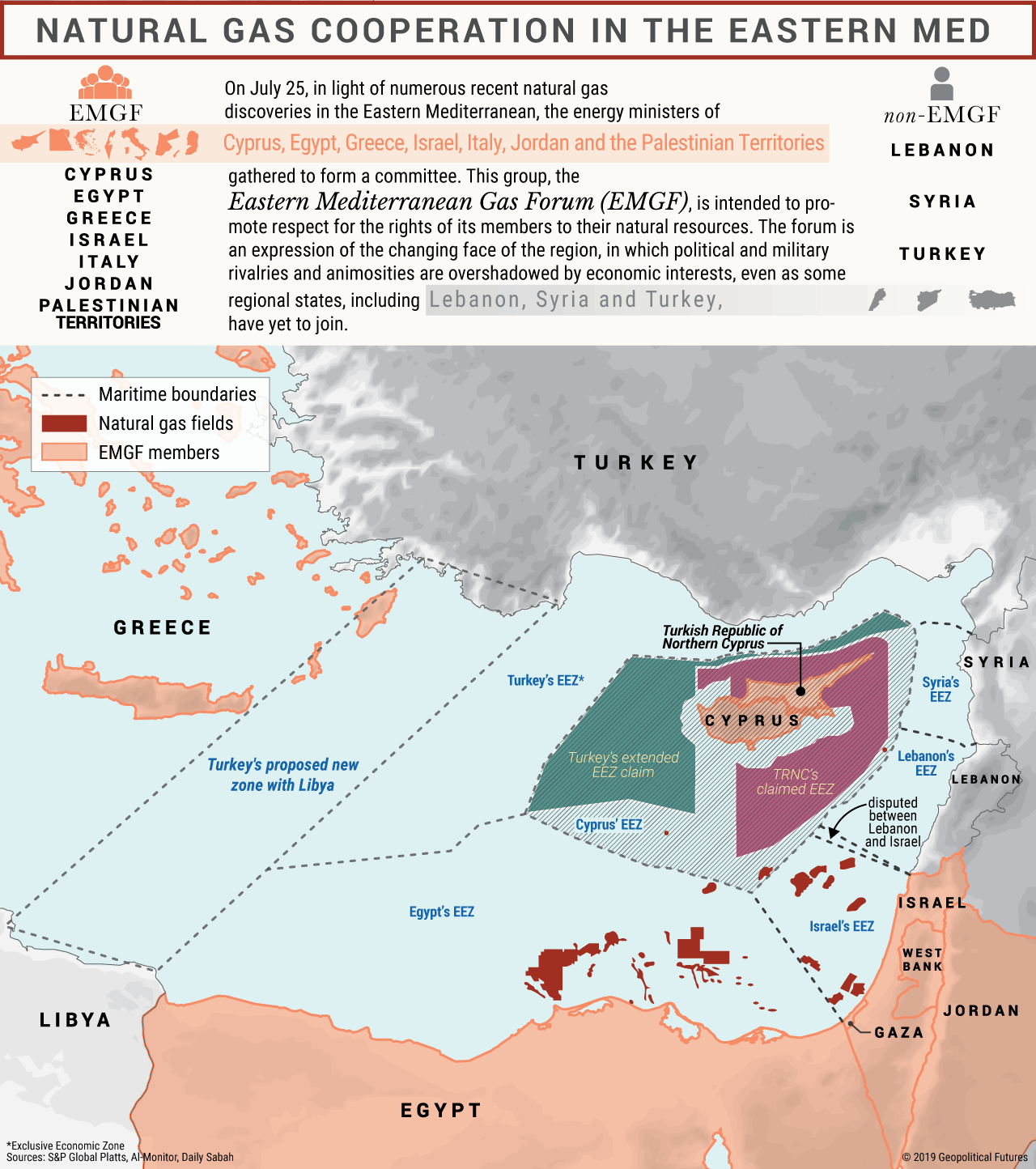

It’s also worth noting that because of the naval limitations of Turkey’s main rivals in the Mediterranean, a full-blown conflict is extremely unlikely. Greece’s armed forces are estimated to total 360,500 personnel, half of Turkey’s roughly 735,000. The two countries possess a similar range of submarines, patrol vessels, frigates and sea mine equipment, though Greece’s naval capabilities are more limited than Turkey’s, as many vessels have been decommissioned and are technologically obsolete. And since Greece’s financial crisis, naval modernization efforts have been sluggish. Athens, however, has the advantage of having regional allies. Greece is a member of the recently launched East Mediterranean Gas Forum, which also includes Egypt, Israel, Greek Cyprus, Italy, Jordan and the Palestinian territories. While the consortium’s primary focus is energy resources, its members have increased naval cooperation and joint training. Meanwhile, Egypt’s armed forces are larger than Turkey’s, and its naval assets are superior in both quantity and quality, since it boasts a greater number of helicopter aircraft carriers and patrol vessels. But only a few of its surface vessels and Type 033 Romeo-class submarines are serviceable, and the country has fallen behind with updates and refittings as its economy lags.

Turkey also has its own limitations, which should cast at least some doubt on its prospects to be the undisputed naval power in the Mediterranean. It has nearly 200 naval assets, including frigates, submarines and patrol vessels, but most of them date back to the 1990s, some to the late 1970s, and require updating. Moreover, Turkey’s possession of numerous short-range, fast-attack craft indicates a limited ability to engage in a distant, sustained campaign in the Eastern Mediterranean – including, for example, a mission to support Libya’s Government of National Accord, which Ankara agreed to assist with a troop deployment back in December.

Still, Turkey’s increased production of conventional naval equipment complimentary to the F-35 and drone capabilities, as well as its plans to bolster its forward bases in Somalia and Qatar and build a naval base in Northern Cyprus, reflects its growing intentions in the region. Ultimately, to achieve greater power projection, what Turkey really needs is aircraft carriers, nuclear submarines and improved aerial defense to sustain supply lines and amphibious operations. So while it has made some ambitious moves and daring declarations of intent, it still has a long way to go. For now, Turkey will continue to posture, posing as a dominant naval power while taking minor steps toward expanding its footprint in the Mediterranean.

No comments:

Post a Comment