By Laura H. Kahn

Many of the viruses and microorganisms that could spark a pandemic or be used in bioterrorism are zoonotic. They are found in domestic and wild animals and have the potential to spill over to people. Yet despite the inextricable connections between the environment and human health, the federal government addresses these areas through a litany of programs housed in several different agencies and funded by different budgetary buckets. The COVID-19 pandemic, stemming as it most likely does from a bat coronavirus, provides a clear example of how animal and environmental health is related to our own. It’s an example the next presidential administration should acknowledge by taking a holistic approach to health security.

Many of the viruses and microorganisms that could spark a pandemic or be used in bioterrorism are zoonotic. They are found in domestic and wild animals and have the potential to spill over to people. Yet despite the inextricable connections between the environment and human health, the federal government addresses these areas through a litany of programs housed in several different agencies and funded by different budgetary buckets. The COVID-19 pandemic, stemming as it most likely does from a bat coronavirus, provides a clear example of how animal and environmental health is related to our own. It’s an example the next presidential administration should acknowledge by taking a holistic approach to health security.

President Donald Trump has shown he’s not interested in improving the federal government’s response to COVID-19, he regularly downplays the severity of the worsening crisis and rejects the value of coronavirus testing and other measures to control the pandemic. His performance has contributed to the disastrous rates of infection and death in the United States. Change will likely have to wait for a new president who believes in the importance of government to benefit all Americans.

In response to catastrophic events, the federal government has been restructured in the past. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, for instance, the Bush administration created the Department of Homeland Security. If Joe Biden wins this November’s presidential election, he’ll have the opportunity to build a government infrastructure that can more effectively protect human, animal, and environmental health, one that could stop disease outbreaks before they spiral out of control. Biden should respond to the coronavirus pandemic by establishing a Department of Health Security—a new interdisciplinary federal agency with a mission to promote, improve, and protect the health of people and the environment as well as that of America’s animals, plants, ecosystems, and agriculture. Such an agency would embody the One Health approach, that many ecologists, veterinarians, epidemiologists, and other experts see as vital to preventing the next pandemic.

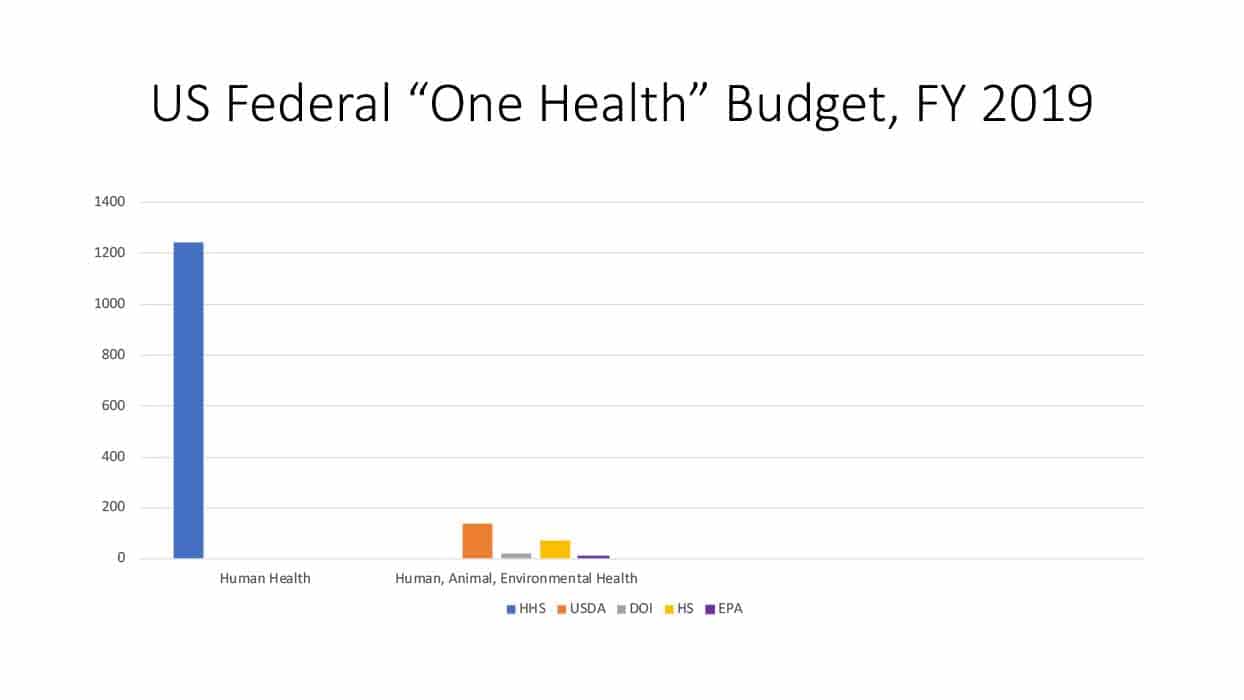

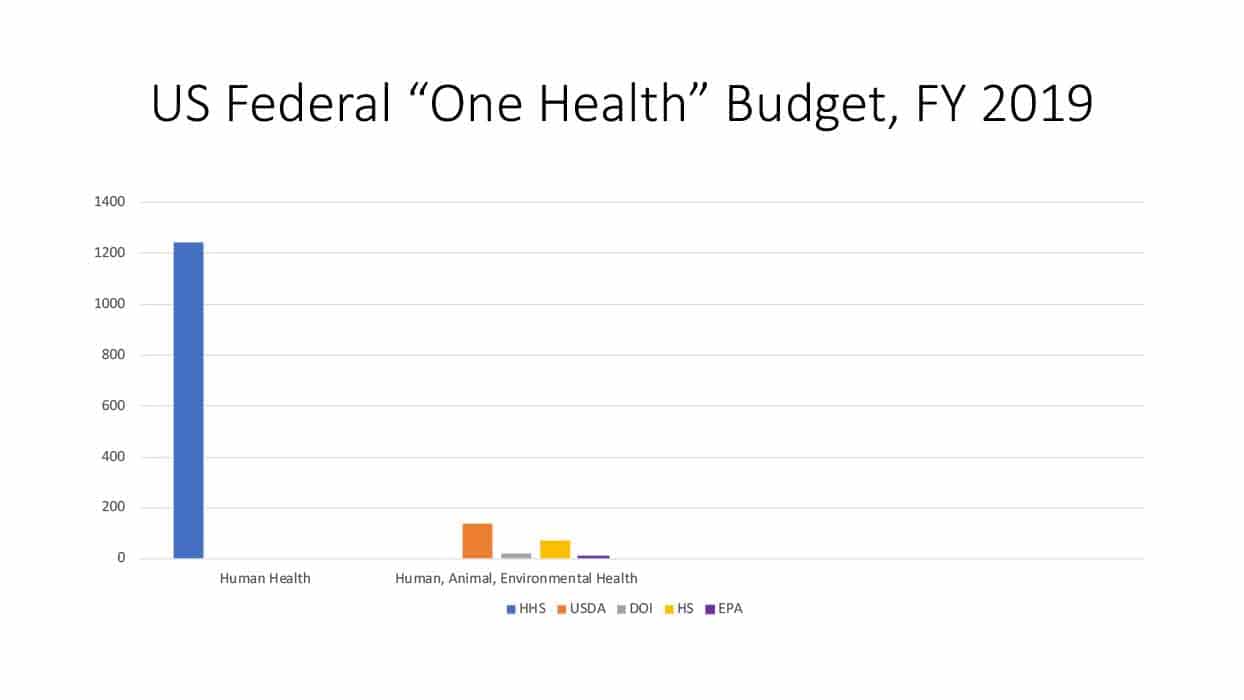

Too little focus on pandemic threats. As it is currently configured, the federal government is primarily focused on one component of disease emergence and spread: humans. While this focus may seem logical on the surface, it downplays the significant role that risky agricultural practices or poor environmental stewardship play in exacerbating health threats such as zoonotic spillover events or antimicrobial resistance. The Department of Health and Human Services’ 2019 budget was approximately $1.3 trillion. Obviously, that’s a huge sum, but 90 percent of the agency’s budget goes to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services which provides medical insurance for the elderly and poor. While critically important, the Health and Human Services Department’s focus on safety-net health insurance programs dwarfs the resources it devotes to disease surveillance and control programs. Indeed, federal funding for disease prevention and control efforts relevant to animal, environmental, and ecosystem health receive minimal funding because their critical roles in protecting human health are generally not recognized.

At 3 percent, the National Institutes of Health—which conducts and funds research on human diseases, including cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and infectious diseases—constitutes the Health and Human Services Department’s second largest budgetary component after the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. While important for understanding diseases and developing new therapeutics and vaccines, the National Institutes of Health is not directly involved in disease surveillance, control, and prevention. The Health and Human Services Department’s preventive health programs that are directly involved with surveillance, control, and prevention such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration constituted less than 1 percent of the 2019 budget. The Health and Human Services Department’s budget is five times larger than those of the other federal agencies that deal with human, animal, plant, and environmental health combined. Figures represent millions of dollars. Credit: Laura Kahn.

The Health and Human Services Department’s budget is five times larger than those of the other federal agencies that deal with human, animal, plant, and environmental health combined. Figures represent millions of dollars. Credit: Laura Kahn.

The Health and Human Services Department’s budget is five times larger than those of the other federal agencies that deal with human, animal, plant, and environmental health combined. Figures represent millions of dollars. Credit: Laura Kahn.

The Health and Human Services Department’s budget is five times larger than those of the other federal agencies that deal with human, animal, plant, and environmental health combined. Figures represent millions of dollars. Credit: Laura Kahn.

Pandemic-relevant programs are poorly resourced. Agricultural practices, animals, environments, and ecosystems are all key drivers of zoonotic disease emergence and spread, but the government programs that oversee these areas are housed in several different agencies and generally receive minimal funding. This diminishes their potential for comprehensive disease-prevention and health promotion efforts. One data point that underscores this problem: the combined fiscal year 2019 budget of four cabinet-level agencies—the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Agriculture, the Department of the Interior, and the Homeland Security Department—is five times smaller than that of the Health and Human Services Department’s 2019 budget, which again, primarily comprises Medicare and Medicaid spending.

These four departments maintain essential health promotion and disease prevention programs involving human nutrition research, food security studies, livestock and crop inspections, large-scale wildlife die-off inspections, border control of foreign pests and diseases, and the monitoring and regulatory oversight of environmental contamination.

Furthermore, the budgets of these agencies often focus on areas with little connection to disease surveillance and control. Nutrition assistance constitutes 65 percent of the Department of Agriculture’s budget for instance. While certainly an essential public health service since people cannot be healthy if they are starving or malnourished, the expenditures mean the department has limited resources to devote to programs like the animal health surveillance program that monitor’s the nation’s livestock and might help stop the next pandemic threat.

Environmental health and zoonotic threats are linked. Environmental health and public health are closely related. People interact with their environment every day by breathing air, eating food, and drinking water, all of which need to be as free from chemical contaminants and disease-causing viruses and microorganisms as possible. While the embattled Environmental Protection Agency monitors air pollution and other environmental contaminants and enforces regulations to improve environmental purity, the Trump administration has rolled back much of its regulatory capabilities and acquiesced to heavy lobbying pressure by corporate polluters.

Nevertheless, contaminated environments and diminished biodiversity adversely impact human health. Air pollution worsens asthma, other lung diseases, and heart diseases. It may increase COVID-19 mortality rates, according to one study on the pre-print server medRxiv. Vector-borne zoonotic diseases such as Lyme disease, which is hyper-endemic in Northeastern states, signify sick ecosystems. Large animal die-offs are another troubling indicator of an ecosystem in poor health. The Interior Department has several programs that monitor ecosystems and enforce regulations, but their funding is miniscule. In general, very little is done to monitor and research the nation’s ecosystems, a major oversight that ultimately impacts human health.

People increase their zoonotic disease risks through contact with animals and their wastes or through consuming other animal protein (e.g. dairy) products. And even though the majority of human infections are caused by zoonotic microbes, there is no Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for animals that conducts disease surveillance. The Health and Human Services Department collects data on animal rabies. The Agriculture and Homeland Security departments have programs such as the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, the National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility, and the US Customs and Border Patrol that aim to protect the nation’s livestock and crops from diseases and pests. Under the Interior Department, the Fish and Wildlife Service and the US Geological Survey are tasked with monitoring and protecting fish and wildlife and collecting scientific data of the nation’s natural resources, respectively, but their potential impact on human health is not recognized. These programs are scattered across departments and agencies with minimal, if any, coordination or collaboration. As they are currently configured and funded, they are inadequate to the task of protecting us against zoonotic disease risks. The US Fish and Wildlife Service samples a bird for avian influenza. Credit: US Fish and Wildlife Service/Diane Borgreen.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service samples a bird for avian influenza. Credit: US Fish and Wildlife Service/Diane Borgreen.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service samples a bird for avian influenza. Credit: US Fish and Wildlife Service/Diane Borgreen.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service samples a bird for avian influenza. Credit: US Fish and Wildlife Service/Diane Borgreen.

Out of the COVID-19 catastrophe, comes opportunity. The next administration should restructure the Health and Human Services Department, the Agriculture Department, the Interior Department, the Homeland Security Department, and the Environmental Protection Agency. As it stands, instead of integrating programs related to human health, agriculture, natural resources, and the environment, the federal bureaucracy has created silos; the One Health approach acknowledges what COVID-19 makes indisputable: they are not.

There is precedence for a large-scale restructuring of federal government agencies. After the terrorist and anthrax attacks in 2001, the Bush Administration created the Homeland Security Department, which consolidated 22 departments and agencies and today employs almost 200,000 federal employees. This massive cabinet-level agency’s mission is to improve domestic security communication and coordination. Creating such a huge agency wasn’t a smooth process. Because its area of responsibility was so broad, officials got into internal disputes and external conflicts with counterparts in other departments, such as the Department of Justice and the National Security Agency, whose mandates overlapped. So many congressional committees are responsible for overseeing the Homeland Security Department’s operations that it’s easy to imagine that officials in the department spend more time preparing to testify on various issues than performing their daily duties. These mistakes must not be made when creating the Department of Health Security.

There are several steps the next president should take to create a federal government more able to protect health and the environment:

Move the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The Social Security Administration is the independent federal agency that administers Social Security. The agency already has a role in Medicare by enrolling people into the program. Moving the administration of Medicare and Medicaid into the Social Security Administration makes sense strategically, administratively, and financially, after all, health insurance is a critical component of financial security for the elderly, the poor, and people with disabilities. This move would allow the Health and Human Services Department to focus its mission on disease research, surveillance, control, and prevention which—as COVID-19 shows, are critical to address the health security threats of the 21st century.

Create a Department of Health Security. The new Department of Health Security would have the mission to promote and protect agriculture, food safety and security, and the health of humans, animals, environments, and ecosystems, an arrangement that acknowledges the crucial roles that the environment, natural resources, and agriculture have in human health.

This department would be tasked with the surveillance of microbes that are capable of jeopardizing national security via active, integrated surveillance of humans, animals, plants, and environments (i.e. soils, waters, and air). It would conduct and coordinate research, provide oversight of laboratory biosafety and biosecurity, implement and enforce relevant laws and regulations, control the import and export of animals and plants, and quarantine and isolate international travelers as needed.

Many of the programs at the Health and Human Services Department, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Agriculture Department, the Interior Department, and the Homeland Security Department should be rolled into this new agency.

It’s likely that bats in China transmitted the novel coronavirus to people, directly or indirectly through an intermediary species. After reporting cases of viral pneumonia to the World Health Organization in late 2019, Chinese authorities shut down a food market in the city of Wuhan that many people suspected was linked to the outbreak, but much remains uncertain about the origins of the pandemic. In any case, the coronavirus has since spread around the world, killed hundreds of thousands of people, and battered the global economy. It’s not enough to protect clean water, block agricultural pests at the border, and monitor diseases with separate, uncoordinated agencies. If we needed any more proof of the links between environmental, animal, and human health, the coronavirus pandemic has provided it in spades.

A new Department of Health Security based on the One Health approach would ensure that health and well-being would become one of the federal government’s top priorities. By highlighting the limitations of the siloed federal approach to human disease, the environment, and agriculture, COVID-19 has created an opening for the next administration to do something different.

For the sake of stopping the next pandemic, let’s hope the next president does just that.

No comments:

Post a Comment