Amit Chaudhuri

The author and critic is spearheading a campaign to preserve the Bengali houses of his birthplace. He explains why reconnecting with the city’s cosmopolitan architectural heritage is crucial to Calcutta’s future

The author and critic is spearheading a campaign to preserve the Bengali houses of his birthplace. He explains why reconnecting with the city’s cosmopolitan architectural heritage is crucial to Calcutta’s future

Iwas born in Calcutta, but we moved to Bombay when I was one and a half years old, maybe in early 1964. The company my father worked in had relocated its head office in the face of growing labour unrest; the move was part of the general egress of industry from the city.

We continued to visit Calcutta once, sometimes twice, a year. My mother’s brother lived there with his family in Pratapaditya Road, in the historic neighbourhood of Bhowanipore, South Calcutta. He is a Jadavpur University graduate and German-trained civil engineer. By the time I got to know him as a child, he’d abandoned his job and set out with friends, establishing a factory that made machines in Howrah, Calcutta’s industrial district across the river Hooghly. Given the political turbulence of the 1960s, the business was a long-drawn-out failure. My uncle, however, never wavered from his faith in the Left.

In 1977, the Left Front was elected to form the government in the state of West Bengal; it then won eight successive elections until finally being voted out of power in 2011. The tenure of the Left in West Bengal was marked by genuine achievements and plenty of failures. Perhaps one of its legacies was to create a microcosm that was entirely out of tune with the free-market zeitgeist whose vanguard assumed power in other parts of the world soon after the Left came to power in Bengal: one thinks of Margaret Thatcher’s election victory in 1979, and Ronald Reagan’s in 1981. India itself embraced free-market deregulation in 1991. Of course, there’s no reason why Bengal shouldn’t have explored an alternative path on its own terms; it’s just that actual faith in what these terms might be was, by the 80s, lacking.

I learnt two things from my visits to Calcutta in the 1960s and 70s, and to my uncle’s house in particular. The first was that there was an alternative to the corporate world I inhabited in Bombay. Culture did not have to be anglophone to be exciting or sophisticated. In fact in India at that time, it seemed sophistication and excitement often lay outside the realm of the anglophone. Second, it appeared that culture and learning did not have to be exclusive to privileged, stable or well-to-do lives. In my uncle’s house, the opposite seemed true: the energy I encountered in it as a child was a remnant of a cultural and political force-field that began to come into existence in the city in the 19th century.

My uncle's house contained an interior narrative whose echoes I'd discover later in other parts of the world

My uncle's house contained an interior narrative whose echoes I'd discover later in other parts of the world

This house was the only piece of property my uncle owned, and it had been gifted to him by his father-in-law. My family came from Sylhet, now in Bangladesh, and they’d lost whatever land or property they might have owned with Partition. This was one of the reasons I never associated the sort of house of my uncle lived in with privilege. Also, Pratapaditya Road had become a slightly disturbed and down-at-heel area by the 1960s. Nevertheless, the house itself contained space and life, and an interior narrative whose echoes I’d discover later in other parts of the world, but never their exact prototype.

These were the house’s features: a porch on the ground floor; red oxidised stone floors; slatted Venetian or French-style windows painted green; round knockers on doors; horizontal wooden bars to lock doors; an open rooftop terrace; a long first-floor verandah with patterned cast-iron railings; intricately worked cornices; and ventilators the size of an open palm, carved as intricate perforations into walls. (Some houses built in the 1940s also incorporate perky art-deco elements: semi-circular balconies; a long, vertical strip comprising glass panes for the stairwell; porthole-shaped windows; and the famous sunrise motif on grilles and gates.)

My uncle’s house no longer stands. It came down as part of the property boom that happened in Calcutta in the 1990s, in anticipation of the Left Front government’s resolve to bring industry to Bengal – a belated stirring of ambition arising from a desire not to miss out on the apparent benefits of economic deregulation that were transforming cities like Bombay, Delhi, Chennai and Bangalore. The destruction of these houses would also be a consequence of the house-owner’s inability to maintain property in an economically depressed city.

Industry never came, partly because of the complex issue of land acquisition as well as the insurmountable populism of West Bengal’s politics. But existing houses and neighbourhoods continued to be destroyed because of the ethos created by “developers” – a euphemism, often, for a new breed of land sharks. This ethos dictated that houses on prime land needed to be bought up and immediately destroyed for the price of the land they stood on. So the houses were never put on the market, and their market value was never determined.

Industry never came, partly because of the complex issue of land acquisition as well as the insurmountable populism of West Bengal’s politics. But existing houses and neighbourhoods continued to be destroyed because of the ethos created by “developers” – a euphemism, often, for a new breed of land sharks. This ethos dictated that houses on prime land needed to be bought up and immediately destroyed for the price of the land they stood on. So the houses were never put on the market, and their market value was never determined.

Among the principal candidates for buying the new “condos” were non-resident Indians: Bengalis settled abroad, mainly in America. They never thought to purchase these houses to live in, though they would, of course, be open to buying such houses to inhabit in London, Marrakech or Goa. Family-owned houses that could no longer be maintained were, meanwhile, frequently sold to developers by non-resident Indians.

Soon, the near-simultaneous purchase and destruction of a house seemed like an inevitability. So, paradoxically, did the acquisition of the accoutrements of globalisation: industry and investment didn’t come to Bengal, but the ancillary features of a deregulated economy – shopping malls, new five-star hotels, multiplexes, gated properties – began to adorn Calcutta.

These days, the prices of new properties here are fuelled mainly by speculation. This means that new housing is hardly a response to demand; it’s an invitation to investors who’d previously have put their money in equity. Advertisements are a reliable integer of the desires of the new well-to-do: in Calcutta (officially “Kolkata” since 2001), adverts for gold jewellery – an attractive form of investment – are ubiquitous. Yet in the last 10 years, I’d hazard a guess that these have been overtaken by adverts for apartments in tower blocks and improbably named (Highland Park, Diamond City) gated enclaves. Rival newspapers carry full-page ads for the same construction on their front pages. Until 2013, property seemed a less volatile form of investment than the market.

But property prices in Calcutta have now reached a plateau, and the only people making money off new flats are developers and estate agents. In fact, they seem to be almost the only people making money in Calcutta at all. A newspaper report revealed two months ago that there has been a dramatic and counter-intuitive surge in “dollar multimillionaires” in this city. The report noted that nearly all of them were making money in real estate.

It was during my travels in Europe in the last 20 years that I realised the neighbourhoods we confront there not only represent the history that produced them, but a history involving communities resisting their disappearance. Without such resistance, no vestiges of the great urban churning of the last two centuries would remain in the world today – in Europe, Australia, the United States and even Latin America. Calcutta, too, was powerfully and uniquely a part of this urban churning (I say “uniquely” because the neighbourhoods and type of house I’ve described above have echoes, but no counterpart, in any other city – in India or abroad).

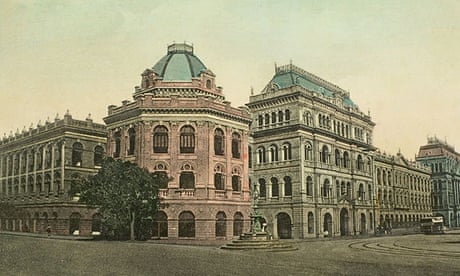

When we speak of Calcutta’s architecture, we usually mean the colonial institutions that the British erected, or the aristocratic mansions of North Calcutta (once called the “Black Town” by the English) built by Bengali landowners. But the houses I’m speaking of were built by anonymous builders for middle-class Bengali professionals: lawyers, doctors, civil servants and professors. They’re to be found throughout the city, from north to south, in Bhowanipore, Sarat Bose Road, Lake Road, Southern Avenue, Hindustan Park, Bakul Bagan, Paddapukur, Kidderpore, Ahiritola and more.

They all possess the family resemblances I’ve enumerated above, to do with slatted windows, cornices, open rooftops and red floors. What is remarkable, though, is that no two houses are identical: a house with a broad facade might stand next to a thin house, both sharing various characteristics – and there are many other ways in which each house you encounter is a fresh conjuring-up or experiment. This makes for an unprecedented, sui generis variety in a single lane or neighbourhood; a variety I have seen nowhere else (think, in contrast, of the identical Victorian houses on a London street). And the style – which can only be described as Bengali-European – is neither renaissance (hardly any Corinthian pillars, as you might spot in the North Calcutta villas) nor neo-Gothic (as Bombay’s colonial buildings are) nor Indo-Saracenic, which expresses a utopian idea of what a mish-mash of Renaissance, Hindu and Moghul features might be. It’s a style that is, to use Amartya Sen’s word, “eccentric” and beautiful, and entirely the Bengali middle class’s.

“Old” is a misnomer for these buildings: they’re the products of the “new” Calcutta, the Calcutta of modernity and modernism that arose in the 19th century and took on a new identity in the 20th; a Calcutta that evaded, became a counterpoint to, took from, and was far richer than both the British-created city and any idea of the “Black Town”.

“Old” is a misnomer for these buildings: they’re the products of the “new” Calcutta, the Calcutta of modernity and modernism that arose in the 19th century and took on a new identity in the 20th; a Calcutta that evaded, became a counterpoint to, took from, and was far richer than both the British-created city and any idea of the “Black Town”.

In a way, many of these buildings, which came up from the early 20th-century onwards, testify to why Calcutta continued to be a political, and especially a cultural, hub in India long after the British took away its status as capital city to contain its revolutionary nationalism in 1911 – and even a century after the “Renaissance”, the efflorescence in Bengali culture in the middle of the 19th century. It’s this Calcutta whose buildings are poised to vanish, and whose survival some of us are arguing for. Two letters were sent in May to the chief-minister of West Bengal: one signed by 15 people who cut across party lines and persuasions; the other by Amartya Sen, addressed to me and written in support of the project.

Among the ideas that have been put to the government is that of “transfer of development rights” – which would see a house-owner sell the developer “rights” equivalent to the price of the land on which his or her house stands, which could then be used by the developer to extend constructions to a commensurate value in another location. Whether or not this model will “work” cannot be ascertained unless it’s adopted.

The letter also refers to the MIT economist Esther Duflo’s observation – glaringly obvious to the outsider who knows a bit about Calcutta’s cultural history, but perhaps not so to the resident who is inured to their city – that, properly showcased, these neighbourhoods (Duflo compares them to Prague’s) could make Calcutta a tourist destination, and bring it the revenue it so badly needs. The ensuing danger of gentrification is a real one, but a fine line divides it from genuine cultural reinvention.

The basic aims of our campaign are these: first, to work towards and arrive at a working solution, however improbable this seems; second, to find new ways of looking at, and discussing what’s important about, these houses and neighbourhoods. Although it would appear that the problem needs to be addressed primarily by the heritage commissions in the city, it’s also clear that “heritage”, as a notion and definition, is part of the problem.

In Calcutta, 'heritage' means we cease to engage with the architectural individuality and difference of buildings

In Calcutta, 'heritage' means we cease to engage with the architectural individuality and difference of buildings

In Calcutta, a “heritage” building is a landmark that is important for either being a significant institutional building, or because a famous person frequented it or lived there. The architectural distinctiveness of the building is a secondary concern, or is a pre-ordained, generic feature of the structure: that is, we already know it qualifies as a heritage structure because it adheres to our idea of what a heritage colonial building looks like.

In Calcutta, “heritage” means we cease to engage with the architectural individuality and difference of buildings and precincts. We don’t periodise, falling back on catch-all terms like “colonial”; or historicise; or describe; or define. Simply put, “heritage” means we don’t see, or think about, buildings. (And yet, even as a rubric to be blindly followed, “heritage” is ignored astonishingly in Calcutta: iconic people’s houses are unmarked and repeatedly destroyed; grade-A “listed” structures are torn down.)

In July, Mamata Banerjee, the chief-minister of West Bengal, whose government succeeded the Left Front’s in 2011, will make her first trip to London. It will be an intriguing event, as Ms Banerjee’s fascination with the British capital is well-known, and has caused mirth in the past. On assuming power, one of her first startling remarks had to do with her desire to turn Calcutta into London. She clarified later that what she meant was that both cities had grown alongside rivers, and that Calcutta could do much more with its riverfront.

If she studies her surroundings on this trip, she’ll discover that Calcutta doesn’t actually look very much like London. The main reason has to do with the two cities’ notably different architectural styles: London’s elegant Victorian, Gothic, Georgian and Edwardian buildings (jealously protected from destruction, on the whole, by conservation laws) are shaped by a distinct Puritanism very unlike the slatted, openness-loving, loiterer-friendly Bengali-European style of, say, Bhowanipore. This disjunction is another reminder of why Calcutta’s neighbourhoods can’t be reduced to colonial history, and must be understood in terms of their own peculiar, cross-referencing cosmopolitanism.

To move on this matter hasn’t been easy, and not only because of governmental inaction and the absence of actual powers where the West Bengal Heritage Commission and the Kolkata Municipal Corporation’s Heritage Committee are concerned. What’s more difficult is people’s inability to recognise the architectural legacy they’ve taken for granted for more than a century, and their mysterious disconnect from the history that produced these neighbourhoods.

To move on this matter hasn’t been easy, and not only because of governmental inaction and the absence of actual powers where the West Bengal Heritage Commission and the Kolkata Municipal Corporation’s Heritage Committee are concerned. What’s more difficult is people’s inability to recognise the architectural legacy they’ve taken for granted for more than a century, and their mysterious disconnect from the history that produced these neighbourhoods.

This is the reason I provided the short personal note at the beginning: to explain my outsider’s point of view. It may be why I see these buildings as I do, without that special Bengali nostalgia that expresses itself, generically, in songs by Bangla bands and in recent Bengali films, which occasionally conflate North Calcutta and any one of its decaying mansions with a sentimental idea of the city’s true heritage. There’s a certain quietism, a sweet apathy, in such nostalgia that I feel even more distant from than the moral superiority I’ve had to confront from people who feel this architecture is too minor and remote an issue for intelligent people to be concerned with.

What’s at stake here is a discussion on urban regeneration – which is connected to, but distinct from, economic revival. For the urban revival of any city, it’s a prerequisite that citizens engage with the spaces, buildings and histories that characterise it, rather than deny those features; that they understand and reuse them. Calcutta, in the last two decades, has largely failed to do this. But the narrative of every great city must contain such episodes of failure, before it begins to look at itself anew.

You can sign a petition to save Calcutta’s architectural inheritance here. A section of this article first appeared in Apollo magazine. Amit Chaudhuri’s latest novel is Odysseus Abroad

No comments:

Post a Comment