By Shruti Pandalai

“If you want to annoy your neighbor, say the truth about them” says an old proverb. Luckily for India, its neighbor decided to throw elbows around everywhere this time and the global town hall is finally convinced. As the international community seeks to shape Chinese misbehavior, it is an open secret that India has been living with these truths since the 1950s. Chinese patterns of provocation have endured for over five decades and efforts at palliation — mitigating tensions without curing the root of the problem — have remained cosmetic too.

The narrative of the great betrayal in India’s public discourse is a legacy of the 1962 war with China. I have argued before that 1962 cemented an enduring discourse of contested perceptions that persists, independent of the climate of talks between governments.

Today, the mainstreaming of anti-China sentiment in India has driven an articulation of policy options where proverbial red lines are being crossed. It is essential now to have a reset in ties, one that ensures that the strategic narrative on China in India’s public square reinforces cold facts and moves on from the shibboleths of the past.

Patterns of Provocation

(Source: depositphotos, Wikimedia Commons)

(Source: depositphotos, Wikimedia Commons)

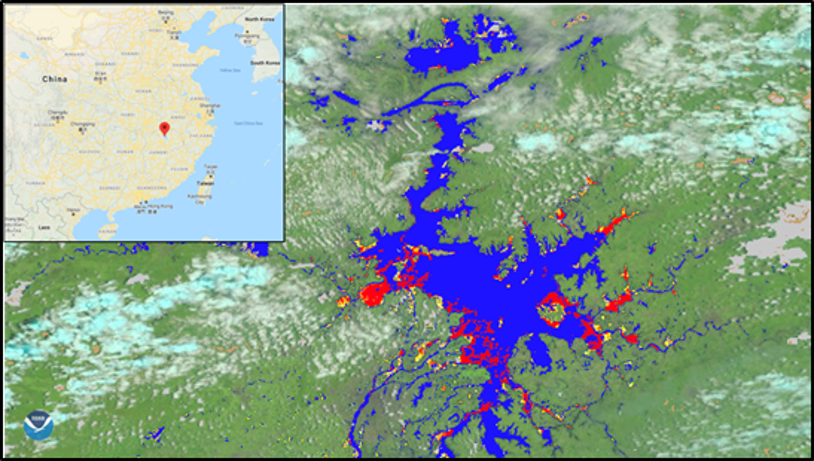

Image: A satellite image from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (dated July 14), which shows flooding at Poyang Lake in Jiangxi Province: flood-affected areas are shaded in yellow, and “severely flooded” areas are shaded in red. (Image sources: Google Maps and NOAA)

Image: A satellite image from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (dated July 14), which shows flooding at Poyang Lake in Jiangxi Province: flood-affected areas are shaded in yellow, and “severely flooded” areas are shaded in red. (Image sources: Google Maps and NOAA)